There are many societal failings this pandemic has brought to light. One currently on everyone’s mind is the lack of available public washrooms.

Writer, binner, and man-about-Fairview, Stanley Q Woodvine, exposed this sobering fact last March at the start of the pandemic lockdown. As most of us hunkered down in the safety of our Covid-bunkers and obsessed about toilet paper, Stanley and other homeless residents of Vancouver were left scrambling to find an open toilet. Recent…er…incidents in Mount Pleasant and other neighbourhoods made plain the urgency of the issue.

Adding insult to injury, recently unveiled plans for the upcoming Broadway Subway transit stations revealed that – once again – public washroom facilities were not to be included. Oh, the places you will go, despite not having places to go! Perhaps Translink should start marketing branded catheter bags for their riders?

100 years ago, Alderman Joe Hoskin proclaimed in local newspapers that “the city of Vancouver is woefully behind the times on the matter of public conveniences”. He insisted that funds be set aside during the coming year for the creation of ample ”comfort stations” throughout the city. A century later, here we are in that same situation — woefully behind the times on the matter of public toilets.

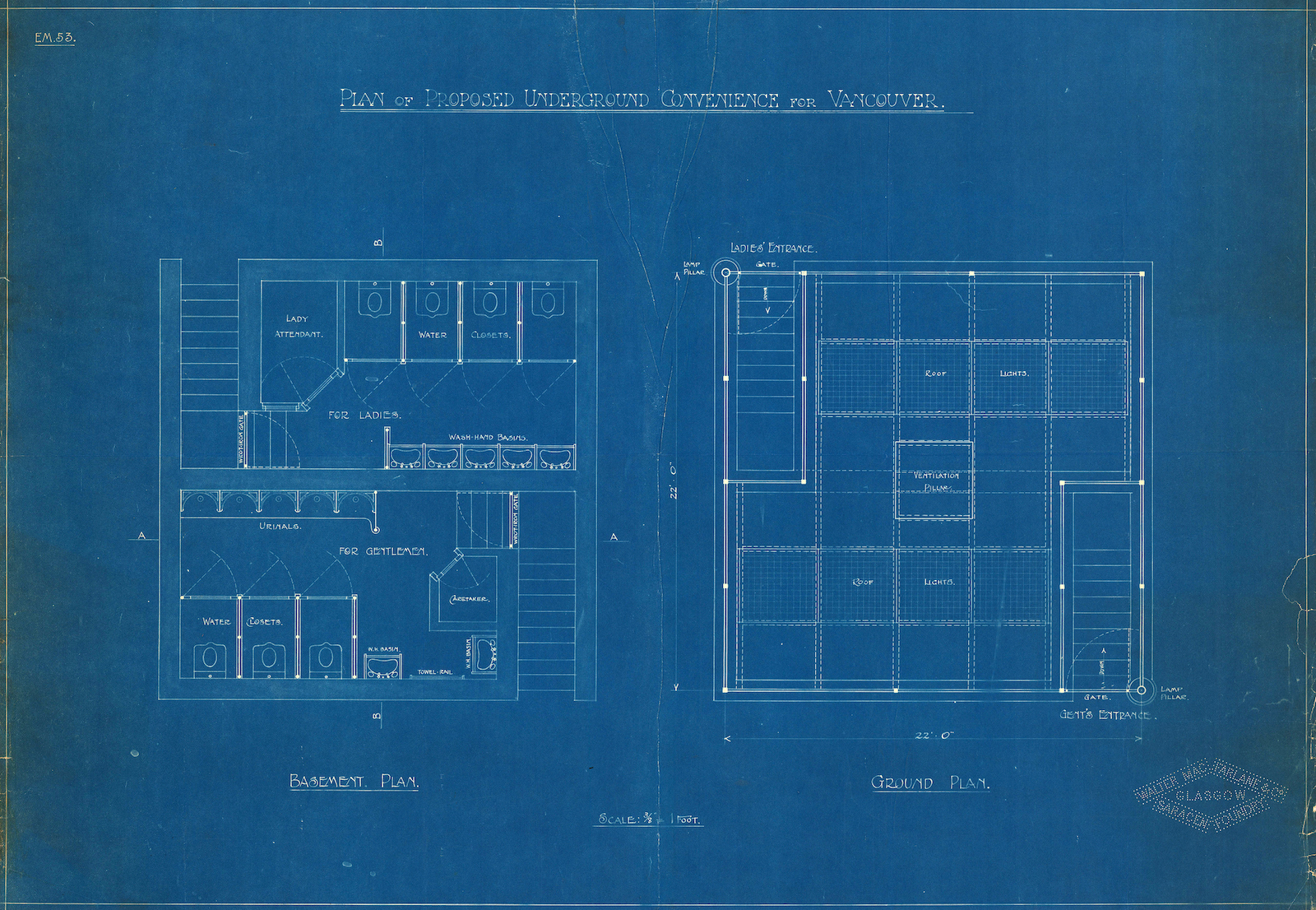

I recently discovered there once was a “comfort station” in my own neighbourhood at the intersection of Kingsway and Broadway. In fact, there were plans for such “public conveniences” all over the city and not just in city parks. The City of Vancouver Archives has many historical architectural drawings for public toilets. Some were built, but many never got past the design phase…

As Vancouver grew from a rough and tumble town mainly populated by men to a city that welcomed women and children, the desire for the “civilities” of city living increased. It was no longer acceptable to simply “drop trow” and relieve oneself in the bushes or by the side of the road.

By the early 20th Century, public toilets were available at some city parks and beaches, such as Stanley Park and English Bay. However, they weren’t as ubiquitous as they are today. And like today, they were only open for limited hours and were generally closed in the winter. If you happened to take your family down to the beach in 1920 on one of those rare, sunny early spring days, you’d be out of luck if you needed to use the facilities.

The first commercial-district comfort station in the city was built at Hamilton Street and Hastings Street, aka Victory Square. 100 years later there is still one there (fully upgraded in 1961). By October 1922, three more comfort stations were to be built using money in the bylaw funds earmarked for the purpose. At that time, the cost to install a comfort station was about $20,000 (about $300,000 today). The proposed comfort stations were to be installed at Hastings at Main, Georgia at Granville (which later became Howe at Robson), and Georgia at Hornby – conveniently located between the Hotel Vancouver, Courthouse (now VAG), and Christ Church Cathedral. However, like today, nothing proceeds forward in this city without a hitch.

Even though everyone agreed that installing more comfort stations was a good thing, there were many complaints about some of the suggested locations of these conveniences. W.R. Carmichael, chairman of the civic bureau of the Board of Trade in the early 1920s, conveyed the opinion of many that “such a public accommodation should be conveniently but not prominently placed”. The most contentious location was for one planned for West Georgia Street in the vicinity of the Hotel Vancouver. Opponents thought it would block traffic and be an “eyesore”, especially to tourists. This begged the question: Can a public convenience be too convenient?

A solution to the battle of the location of one of the conveniences’ was found in Mount Pleasant in October, 1923. A petition from the neighbourhood’s business owners was presented to the city, asking for a public convenience to be established in the heart of the commercial district near Main and Broadway. Alderman William R. Owen, a Mount Pleasant hardware store owner who believed in “necessities before fads and frills”, met the request for an uptown comfort station with approval. It was to be the first and only such convenience outside the downtown core. Funds for this station were to come out of those destined to finance the highly disputed West Georgia Street facility.

By 1928 there were four comfort stations in the city – three downtown and one at the corner of Kingsway and East Broadway beside the old Mt. Pleasant School. A replica streetcar info booth installed in the late 1980s beside the west parking lot of Kingsgate Mall now stands in its location. Wouldn’t it be fun to combine the two and have a streetcar styled public washroom installed there now?

Comfort stations were owned by the city but maintained and operated by independent contractors. In the mid-1920s this cost the city $180 per month per station. Stations were open from 9 AM to 9 PM and contractors would pay attendants to help staff their station. Members of the public could access the toilets at no cost, but under terms of their contract with the city, station attendants were allowed to charge one cent for a towel and one cent for washing privileges. They were also allowed to operate shoeshine stands and other approved concessions, making the whole operation more profitable for operators and more attractive to customers. Some of the comfort stations were equipped with private pay rooms for those who desired a more exclusive public toilet experience.

By the 1940s the city was expanding and the demand for additional comfort stations around the city was increasing. Although additional comfort stations were petitioned for at Broadway and Granville and Broadway at Commercial – both busy commercial and transit hubs – they were never realized.

“Vancouver has the classiest and most used comfort stations west of Toronto according to Grey Cup fans in the know”, declared the headline from a November 30, 1963 Province newspaper article. You know that if tourists are raving about your public toilets, they were something to be proud of and supported. What happened to change all that?

Curiously, a year later, in the era of “civic modernization” and the war against “urban blight”, Alderman Ernie Broome led a campaign to remove all four of the city’s comfort stations. He believed they were no longer needed and cost the city nearly $30,000 (or about $250,000 today) a year to operate. Attendants at the four stations challenged Alderman Broome to come down and see for himself how busy they were – especially on Sundays when most establishments were closed. According to Allan McIver, attendant at Victory Square in 1964, “one day there might be 1,000 persons and another 100”.

Ultimately, a pair of shopping mall development projects resulted in the elimination of two of the city’s comfort stations in the early 1970s. The redevelopment of the old Mount Pleasant School site as Kingsgate Mall saw the demise of the only free-standing public washroom in Mount Pleasant. Downtown, the construction of Pacific Centre saw the elimination of the old comfort station on Howe at Robson. Ironically, it was replaced by the old Eaton’s building, dubbed by many as the world’s largest urinal.

Though as busy as ever, by the start of the 21st century, the situation at the city’s remaining two comfort stations became even more desperate. In addition to their intended usage, illegal activities such as drug transactions and drug use were taking place there. As a result, the Vancouver Police Department wanted to eliminate the toilets. In a piece he wrote in 2000 for the Vancouver Sun about the current state of affairs for the city’s comfort stations, John MacLachlan Gray thought this response by the police was “illuminating, for it suggests both an anal-retentive aspect to our culture and a civic bureaucracy in denial.”

Gray was also confused, as are so many of us, as to “why the lack of public washrooms in the Sky Train system? (Forty-two million riders a year, zero toilets, you do the math).” Like today, the problem in the past was getting the corporate bodies involved to commit to funding them. For example, in 1944 there was interest in getting a comfort station at the terminal of the Stanley Park streetcar line. City council appointed a special committee to confer with the BC Electric Railway Co. (a precursor to Translink) to divide the cost of a station. The Park Board got involved and offered to pay 1/3 of the cost if the other two parties confirmed they would share the rest of the expense. I’m not quite sure why an equitable solution like this couldn’t be reached today with the City, Translink and other stakeholders in order to get washrooms installed in the Broadway Subway transit stations. Cities all over the world – Toronto, Paris, New York, London, Montreal – have toilets in or near transit and interurban train stations. Why can’t we?

The addition of automatic toilets around the downtown core in the last 10 to 15 years has helped, but doesn’t address the situation in other parts of the city like Mount Pleasant. We can’t continue to rely on private businesses like restaurants to pick up the City and Province’s slack in providing accessible toilets to the public. It’s all in the name: public conveniences. They should be convenient to the public. Why? Because as the title of one of my favourite kids’ books says, “everyone poops”, and sometimes we need to go when it’s not so convenient.

This is the first article I read when I come to this site – always a really informative, interesting read.

Aw, thanks, Faye! Glad you are enjoying them.

Great story Christine. As a retiree with a history of an Inflammatory Bowel Disease, I’ve long appreciated the facilities provided in Vancouver’s community centers and some city parks. But it’s very strange to me that the new $2.83 billion Broadway subway project has not a single dollar for washrooms. Apparently none of the decision makers on that project are transit users with a health challenge.

Thanks Callum. And thank you for sharing your own story. I personally find it reprehensible that washrooms are not included in this latest mass transit project.